In the past I’ve previously written on camera setting and optimization which means pushing your gear to its limits to increase the quality of your images. Today, I’ll go over the latest techniques and demonstrate how to use them together to produce the best quality images that you could possibly capture.

The first step is to establish a basic premise is: There is the best method to set the camera to capture a particular image. In addition, there’s also a perfect method of setting you post-processing program and settings according to the output medium you choose to use.

There are times when you’ll need to sacrifice little bit of quality in order to make the proper camera settings. If you have to capture a picture at f/1.4 to get an extremely shallow field of view, then go for it. Don’t limit yourself to f/5.6 simply because that’s your lens’s ideal aperture.

There is often significant flexibility in the settings you select It can be difficult to determine what settings will result in the best image quality.

This article is for. I’d like to believe that it’s one of the most important projects I’ve done with Photography Life; it’s my method of distilling the various ideas we’ve discussed into a comprehensive explanation of how to maximize quality of the image. It’s a bit long and sometimes difficult, but it’s effective. This is the procedure I try to follow for every photograph however I’m not sure if I always succeed.

The only aspect I left out included flash photography. Flash photography is complicated enough to warrant its own section as well. This one’s full of aplomb.

The details below are applicable regardless of the topic or genre you’re taking pictures of. Let’s begin with the camera equipment:

1. Camera Equipment and Image Quality

I’m not going to avoid mentioning that the camera you choose to use system can affect the quality of the image. Certain cameras are simply better resolution or superior high ISO performance than other. Some lenses have sharper images as well.

However, my intention isn’t to suggest purchasing new camera equipment if desire better quality images. The goal is to help you enhance the quality of your photos using any camera.

If your current camera isn’t able provide the quality of images you require even with the most perfect technique, I’d be shocked. I would also suggest using a different camera. However, if you’re here I’m going to assume that you already have the equipment for the task in hand.

The only suggestion I’ll mention here is this simple Make sure you use tripods!

Certainly, there are instances when tripods won’t work, such as the majority of photographs taken on the street, in aerial underwater photography and some others however, for the moment it’s all about maximising the quality of images. If you think a tripod won’t be effective for your photo then, you should utilize one. It’s more beneficial than everything else we’ve discussed.

Let’s continue to expose.

2. Best-Case Scenario Exposure Settings

Let’s begin with the best settings for optimal scenarios photos.

When I say “best-case scenario” I’m talking about the situation where there are no restrictions regarding the shutter speed you can shoot at. The camera is mounted on an tripod and nothing in the frame is moving (or anything that moves is designed to blur, such as a waterfall).

I’ll go over the exceptions later however they’re all variations of the method below.

2.1. Aperture and Focusing

Before setting anything, make note of the lenses “target” aperture and where it will have the best results on flat test-chart-like.

For contemporary lenses, it ranges between f/4 and f/8. However, it is important to try your own lenses out to ensure this is the case you are getting the best quality, or at a minimum look up reviews online that evaluate factors like sharpness.

The key is this point: The aperture (call it f/5.6) may be the goal for clarity, but it doesn’t mean it’s ideal for your photograph. Most of the time, you’ll require smaller or larger depths of field, which f/5.6 provides.

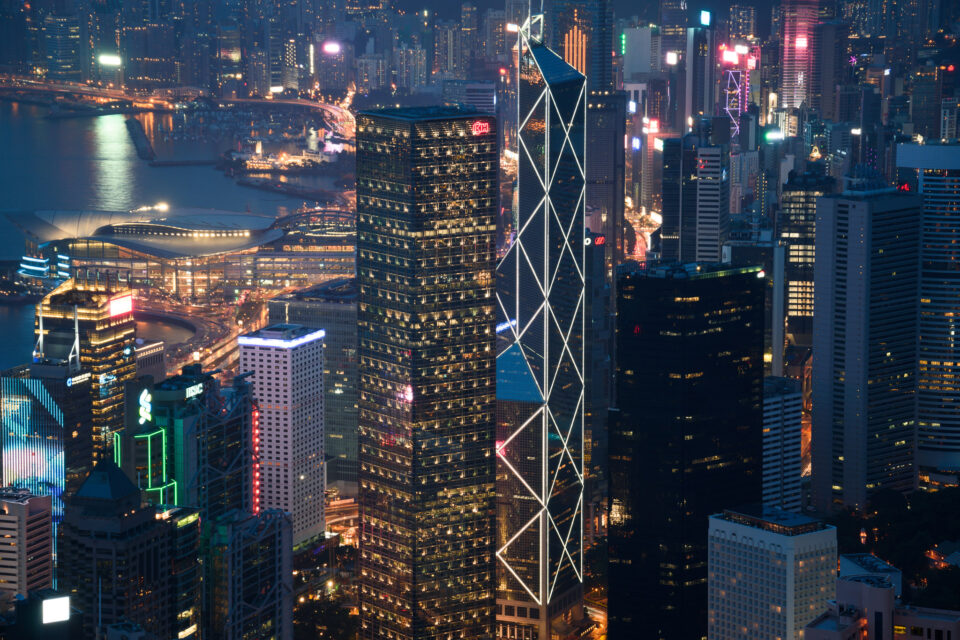

However, a shallow depth of field will not always be the goal. If you want your image to appear clear from top to bottom, then you’ll have to exert a little more effort. Particularly, you’ll need to have to manage the depth of field and the diffraction. It’s a daunting task however, it’s not as difficult as you imagine.

I’ve discussed the best method several times before It’s a good choice as it creates the most sharp and evenly backgrounds and foreground areas within your image. It’s not always your aim – in some instances you’ll have to prioritize the sharpness of your foreground or background over the other. However, it’s an excellent standard.

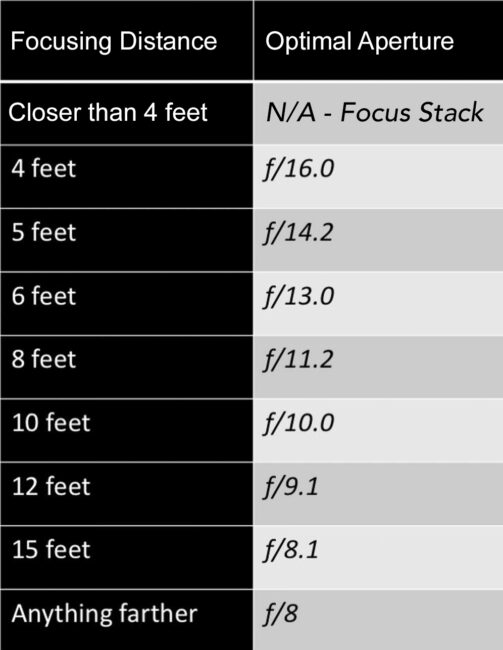

In essence, you focus on the double distance method and then consult charts to identify which aperture is the most mathematically optimal for best image quality. The way to describe it is:

- Frame for the picture.

- Choose the nearest object to your photo that you would like to be clear.

- You should focus on something twice the distance from the object. Therefore, if the nearest thing in your photo is a grassy patch about a meter, then concentrate on something that is just two metres away.

- Utilize a diagram drawn from our best aperture guide to determine which aperture is the most balanced between Diffraction and depth of field.

- Adjust the aperture.

Making the chart is where a lot of people are stuck however, it’s not particularly difficult. It could take around 10 minutes of work to cut down the charts I’ve made to something that you can use with your equipment. The entire process is described in our previous article.

For instance, the table (in feet) for the Nikon 20mm f/1.8 AFS is shown below. It is important to note that this lens has a an “target” aperture that is f/8. It cannot stop below the f/16 limit.

If you’re not keen to use charts while out in the field I’m sure you’re not alone. Another alternative – that I hope doesn’t sound crazy – is to keep the chart in mind for the gear you use every day. It’s simpler with an flange lens than zooms, but it’s doable regardless.

This article is all about maximising the quality of images in every way. If that’s not the goal you’re after do not follow these steps. A professional photographer is able to determine the best aperture and focusing distance generally, so there is you don’t need to follow the procedure previously described. Choose whatever works for you.

2.2. ISO

Set the base ISO And you’re done.

The majority of the aspects of image quality involve capturing as much light as you can. If you can get the smallest ISO value it is possible to use an extended shutter speed to collect more light while trying to avoid overexposure.

You’ve probably heard that certain cameras come with special “LO” ISO values that are less than the base ISO. Avoid using them as they’ll reduce you’re dynamic range. Use your camera’s base ISO amount instead.

2.3. Its Shutter Speed, ETTR

Then, choose a shutter speed that will expose to right (ETTR). I’ll go over two different methods for doing this in a minute.

ETTR is all about capturing the most light possible without collecting excess light and exposing the most important areas of your image.

Somewhere along the way photographers created an idea that ETTR is a way to capture bright, overexposed photographs. Actually, in a lot of cases (high-contrast scenes in particular) the ideal ETTR image is considerably more dark that what a camera’s matrix meters recommends as the default.

ETTR is not concerned with taking a picture that appears bright. It’s all about keeping all of your crucial highlights. Here’s how to do it:

Method One Hetogram

The simplest way to confirm whether you’ve been exposed to the right level is to look at the camera’s histogram and determine whether any channels of color are underexposed.

This isn’t a perfect technique, mainly because the histogram of your camera is built on your JPEG preview. This means you’ll see an extremely different histogram with “Vivid” as opposed to “Portrait” image control.

If you are heavily dependent on this method then you’ll need to choose the least neutral picture control as it most mimics the RAW format.

Oh, I’ve forgotten my usual statement that you should Shoot in RAW and not JPEG. Particularly if you’re the kind of photographer who is a fan of these kinds of articles in the hope of maximising the image’s quality.

Method 2: Spot Metering

An alternative method to figure out the ideal exposure is to spot-meter on the brightest area of your image. After that, you can dial in positive exposure compensation in order to make this area of your photograph with a high-contrast highlight, specifically brighter than you can get it to ensure that you are able to be able to recover 100% of it during post-processing.

It could take you a few minutes out in nature to determine which part of your photo is. And the consequences of picking the wrong location will almost certainly be overexposure. However, at the end of the day, it’s not at all difficult to achieve on the field, especially when you’re shooting slow-moving photography of landscapes.

But the precise “100 percent recoveryable value” is something that you’ll need to determine prior to time for your camera. For my Z7 it’s +2.7 EC (though I’ll often use +2.3 EC instead, to create some kind of security net). Picture Control does not matter because it’s independent of the camera’s meters.

In a side note the technique of spot metering to show the most vibrant hue of your subject optimally it reminds me like Ansel Adams’s system of zone, but little more digital. It’s pretty exciting if you are interested in me.

UniWB

If you are using the histogram technique, the most effective method of setting both your tint and white balance to improve the accuracy of your histogram is to create “unitary white balance” or UniWB.

In short, use the most flat possible settings for controlling your camera’s image. After that, make the “tint” so green that it is you can and make sure that the white balance is set on your camera to ensure that green and red color channel increasers are close one to one another (and at least 1) as you can.

You can determine the exact white balance at which this happens by reviewing your images in EXIF viewer software. (For MacOS, I use ApolloOne since it’s free, but there are many similar applications.) It’s identified by the names of “Blue Balance” and “Red Balance” in the majority of EXIF viewers. For it, like the Nikon Z7, for example it’s the UniWB value is 4945 K, but it isn’t possible to set the precise value, and you must choose 4940 or 4950 as an alternative.

Color Filters

To take this idea to the extreme, you could utilize a color filter on your camera to counteract how the channel in green typically is able to record before other channels in daylight. I suggest a 30% magenta filter (specified as cc30m or Cc30p by many filter companies) or an 40% magenta filter (cc40m or Cc40p).

A side note: If you are using the magenta filter with UniWB the camera’s preview image will look pretty normal.

It’s an extremely esoteric technique for maximizing image quality, but it does the job. It will give you (at the very least) approximately 2/3 stops of exposure using the cc30m or cc40m filters before you begin exaggerating some of the channels you have. This isn’t bad, akin as using an camera having a an initial ISO 64 rather than 100.

3. Maximum Exposure when You’ve Got A Shutter Speed Limit

All of the above information assumes you can choose any shutter speed you’d like without difficulty. However, this isn’t always the case.

When you’re trying freeze a moving object or take photos handheld there’s likely to be a limit to the length of time you could set the shutter. This, in turn, requires adjustments to the ISO and/or aperture you choose to set.

This is the part where things start to get messy.

3.1. Shutter Speed

The first thing to remember is that each photo is a perfect setting of the shutter. If you are in the range you want, you should not go beyond it. Motion blur in excess can destroy a photograph within a matter of seconds.

What rate of shutter should you choose to set? Ideally, you should select the highest shutter speed that fully stops the motion of the image. In this case when you remove motion blur using a 1/125 second shutter speed, or even faster then 1/125 second is the best shutter speed for you to use. It’s the longest exposure that has zero motion blur. This means it will capture the maximum amount of light possible under the conditions.