While looking over a beautiful photograph, I can overlook the fact that many were shot in a fraction of second.

I am reminded of this after having read the opening paragraph of “Tete A Tete” a book focused on Cartier-Bresson’s famous portraits that was written by the famous expert on art history E. H. Gombrich. In the book, Gombrich writes that when taking a look at the majority of photographs of people, we can be 100% certain about one factor: “It is that these individuals and couples haven’t shown precisely the same aspect in their pictures for more than an time. At the same time, they could have changed their eyes, turned or tilted their heads …. Each of these actions could drastically alter their appearance.”

In a sense, Gombrich reworks Cartier-Bresson’s concept of the “decisive moment,” which refers to the “split second that shows the true nature of the situation.” But what really struck me was something that was more useful: Nearly every photo we shoot is created within a matter of seconds, and we don’t notice it when we take it. It happens too quickly.

A selection of photos I have included in the exhibits below demonstrate this: For example David Katzenstein’s group photos in his series “Outside The Lorraine A Photographic Journey to a Sacred Place,” are mostly candids, and are captured using high shutter speeds. After the camera had frozen the subjects the images continued to move. However, when you look at photographs of famous photographers such as Katzenstein the iconic photos generally aren’t of a an instantaneous quality. They are much more solid.

How do you achieve this? I’m convinced that there are at minimum of three ways that photographers are able to accomplish this:

- Connect to the community Photographers such as James Van Der Zee, who live in a community, are able to constantly examine their subjects. The dazzling quality that Van Der Zee’s collection of work is in part due to his decades in a long-lasting connection to his local community. It is situated in Harlem situated in New York City.

- Connect through the journey or joining in an organization: David Katzenstein formed an association by taking the journey towards The Lorraine Motel, in Memphis–the location of the Rev. the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. He took pictures of people who have made their own versions of pilgrimage to Memphis. Furthermore, his work is currently on display in the city.

- Connect to an idea or a concept:Photographers and artists have also utilized concepts and ideas to give their works a deeper significance. This is what happened in the exhibition of fine art “Gillian Wearing Masks: Dressing in Masks,” currently at the Guggenheim.

James Van Der Zee’s photographs: An Portrait of Harlem

What makes the fine art photography exhibit “James Van Der Zee’s Photographs: A Portrait of Harlem,” fascinating is the fact that not only was Van Der Zee capture both formal portraits and work that was documentary in style as well, but he also did it for decades in one place: Harlem. The exhibit may contain only 40 photographs however the photographs are powerful in the narrative they tell.

According to curator, Diane Waggoner, Van Der Zee was a patron to the middle-class Black clientele and produced studio portraits for a period of a few years. Many of his images are of portraits for weddings, engagements, confirmations and many more. Van Der Zee has also took many group photos of religious and literary societies, social clubs as also sports and military teams. The exhibition also contains Van Derzee’s photographs from his documentary of Harlem nightclubs and storefronts.

Whatever the subject matter, his photos “served as an object of praise” within the community according to the curator. However, Van Der Zee’s important contribution might be the result of a in the form of a complete and nuanced portrayal of Harlem as well as a narrative of Harlem during the 20th century.

Out of The Lorraine: A photographic journey to a sacred Place

Certain locations around the globe such as those at the Vietnam Memorial located in Washington D.C. and the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York, allow visitors to honor those who have lost their lives to tragedy. They can also provide great locations for photographers but such initiatives must be handled with caution.

An upcoming photography exhibit, “Outside The Lorraine Motel The Contemporary Pilgrimage” includes more than 90 images of which David Katzenstein captured in 2017 near the scene of Martin King Jr.’s assassination. It’s also a great example of how to take photos at an important spot. To begin, Katzenstein was careful not to disrupt the experience of museum patrons. Gay Feldman, who curated the exhibit, writes that as the photographer was preparing for the shoot He positioned himself “in an inconspicuous and discrete way outside of in the gallery.”

It’s fascinating that the most intriguing images depict people photographed from behind so that faces aren’t visible. This way, Katzenstein gives the body speech of his subjects a an sculptural look. You feel that you feel the emotions they feel when they gaze towards the spot in which an prominent people from the Civil Rights movement was assassinated.

“Pilgrimage is a central concept in the work of David Katzenstein,” says Feldman. This project forms part of his wider collection of work, “The Human Experience,” which is an accumulation of his artistic explorations in visual form which span more than 30 years.

William Eggleston: Black and White to Color

William Eggleston (born 1939) his work, which is currently on display in the Jackson Fine Art gallery, is often mentioned as being one of the most important artists to make color photography an art medium that was recognized by the world of fine-art. However, as the B&W image “Untitled (girl moving)” illustrates in this exhibition, Eggleston could also capture stunning monochrome photos and frequently especially towards the beginning the course of his work. The new exhibit is designed to raise his B&W work in tandem with his photography in color.

But what was it that got him interested in colors in the first in the first I find it fascinating to hear from photographers about the reasons why they decided to experiment with something different. On the Jackson Fine Art gallery website you can find an interview with the photographer that addresses this exact question.

Eggleston states, “I had seen a number of Technicolor films and I was having visions of amazing colors that I was trying to create in my head. I was sure it would work. I went to the market and bought several rolls. I believe that the very first one was taken at the old Montesi’s (a Memphis supermarket] during late afternoon sunshine.”

in the video interview Eggleston mentions in the interview mention that he bought the photographs developed in a local drugstore. “I received the drugstore photos back, and an year later, I put together what I believed to be the most impressive ones, and also several prints that were professionally printed at Chicago ….” Eggleston also reveals the reaction he got on an excursion in New York not long after his first breakthrough in the use of color “When I finally had enough printed prints, I presented John Szarkowski [director of photography at MoMAthe MoMA] what I was up to. They were shocked that anyone from the South was doing anything so sophisticated in photography.”

Time and Face Time and Face: Daguerreotypes to Digital Prints

Over 100 images of this group show, which was curated by Roberto C. Ferrari, which spans from the 1840s through the present which includes photographs made by using the majority of photomechanical processes starting from the early days of photography using analog cameras to our modern digital age. There’s also a mix of styles, such as portraiture, photojournalism as well as documentary photographs. The exhibition features a specific group portrait, which was particularly interesting the curatorial team. “Class of 1850, Department of Chemistry, Columbia College, Ca. 1857-60″ illustrates the first class of chemistry at Columbia and is accompanied by Prof. Charles Joy and his laboratory assistant.

Ferrari is referring to the photograph when he discusses an interview did about the exhibit published in Columbia News where he writes, “One of the more interesting findings… are an extremely rare salted paper image from the period 1857-1860 in which are the five first students to study Chemistry at Columbia along with their instructor, Charles Arad Joy, as well as a young Black lab technician. …. The chemical characteristics of photomechanical reproduction were significant to Chandler and the resulting result of his curiosity has made Columbia among the first institutions to collect photography prior to places similar to those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art ever did. From a historical and portraiture view However, one of the tragic aspects of this photograph is that, while the students and their instructor are identified, we can’t continue to study, determine the Black teenager, who was an University employee. The loss of identity for the student can be seen as an action of denial that could be seen as a an aspect of systemic racism in the institution.”

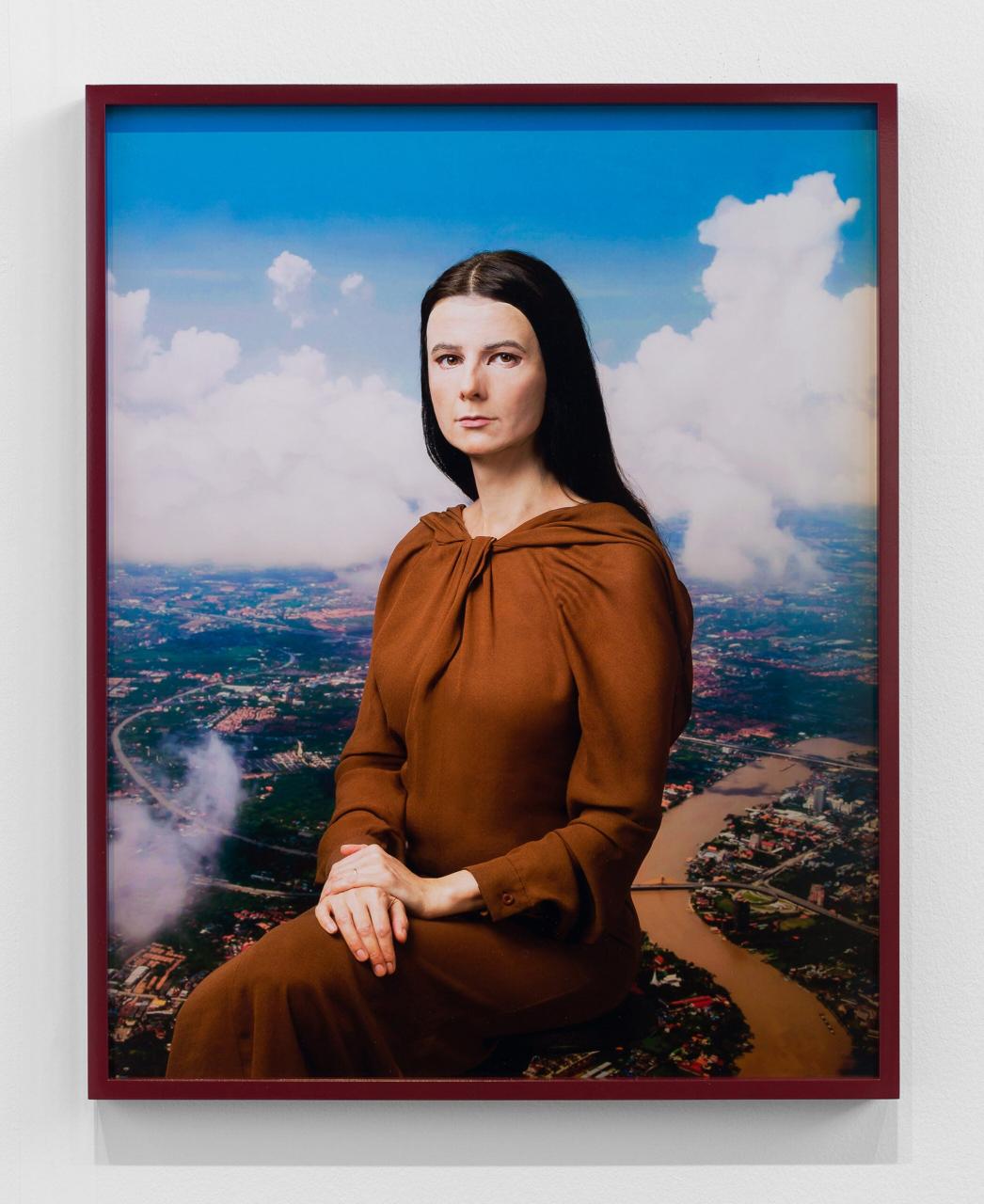

Gillian Wearing: Masks

In the world of contemporary art I think a touch of humor allows fine artists to get the attention of elites of the arts as well as people in general. In the exhibit “Gillian Wearing: Wearing Masks,” the artist (Gillian Wearing) is doing just that by using a peculiar and slightly bizarre style of comedy. However, I believe she’s successful because it enables her to make intriguing remarks about self-portraiture as well as its place in the world.

The show is made up of different mediums, however most of the work featured that is displayed is photographic. The theme that runs through the show is that every piece depicts the artist’s gaze looking into the face of another or a mask. Masks are of her in various stages of her life and masks that depict other characters, including family members and famous figures, like The Mona Lisa. It’s also difficult to not notice an bizarre irony: the show is about an artist who wears masks in a period where we all wear masks due to Covid-19.

To get more fully, there’s an informative video available on Museum’s YouTube channel where Nat Trotman, the curator describes the process of Weaing: “Masks are a central element in the work of Wearing. They appear in her photos as well as in her videos, paintings and sculptures in both the form of props as well as as metaphors. In the context of Wearing Masks, the mask is a way to talk about the small performances every one of us performs each day as we perform our lives as citizens and with our families in all of our interpersonal interactions.”

Left Side Right Side

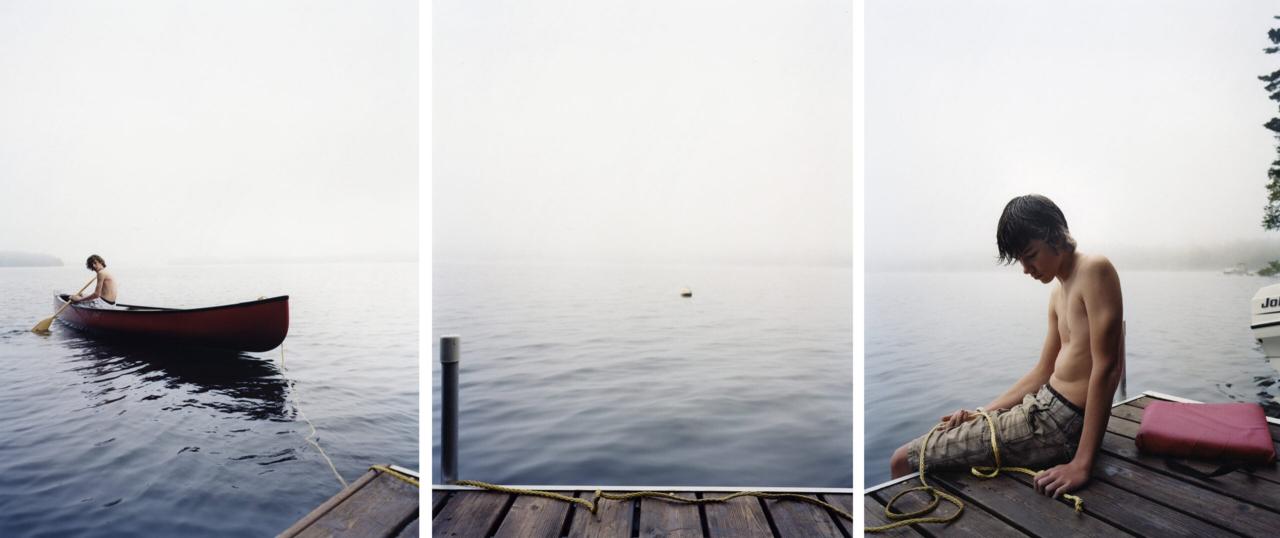

This show, which includes works from a range of media including prints, video, photography and paintings, as well as sculptures — have been focusing on the field of portraiture as well as “its expression in the art of today.”

The provocative title of the exhibit actually derives in the name of an earlier short video, “Left Side Right Side” which was the result of artist Joan Jonas’ early exploration of self-portraiture using video. (You can look at an image of the exhibit on the site, which includes an audio clip that features Joan Jonas.)

In the exhibit, you can see a stunning, massive triptych image, called “Boys Tied,” by David Hilliard an artist who frequently creates large-scale, multi-paneled works that are based on his own life or on the lives of others close to him. When he made this photograph it was in 2011. Hilliard was working on a set of photographs that examine the often conflicted masculinity of men and the environment that it is able to develop and expands.

According to a press release in one of his exhibitions in the Yancey Richardson Gallery, “In this collection of works the boys of all years go through a series mental and physical challenges, which serve as life-long benchmarks or markets in a sense. They love, hunt blood, compete, fail…but ultimately persevere.”